My Sixth Great-Grandmother

Parents: Unknown

Husband: Pierre LeBlanc

Mother of Rose (about 1755), Silvain (1769), Jacob (1773-1773), Marie Louise Devine (1774)

Before an introduction of Anna Landry is made, imagine a young wife and mother about twenty-four years old, given one day to arrange to leave her home forever, prepare her children and board a ship to an unknown destination in the year 1755. What does she take with her? Was she given enough time to take the things she treasured most? What must she leave behind? Will there be room for an iron pot that cost so much to buy? What will happen to vegetables recently harvested from the garden that cannot be taken? Had her husband carved a cradle for a baby that must be left behind? Can the spinning wheel be taken apart and packed?

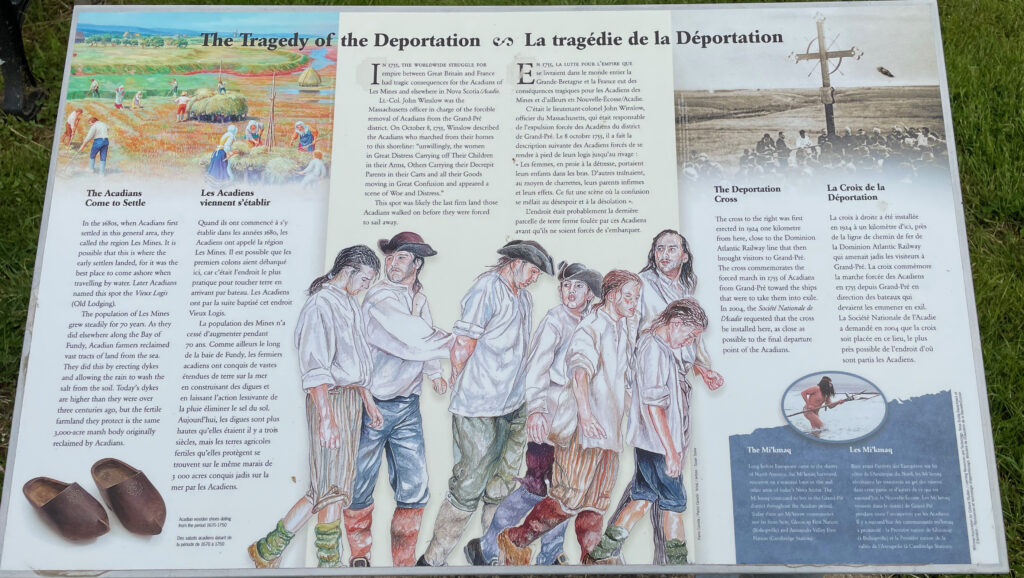

Most likely, Anna’s husband, Pierre LeBlanc, was locked in the Catholic church St-Charles-des-Mines in Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia, when the Acadians were told they must forfeit everything except their money and household goods and leave Grand-Pré. For many years, the Acadians had lived in Nova Scotia knowing that the British wanted them to take an unconditional oath of allegiance and that the British were encroaching on the lands the Acadians had developed into fertile farming land over the last seventy-five years. Nevertheless, no one ever expected to be deported, especially in such a brutal manner.

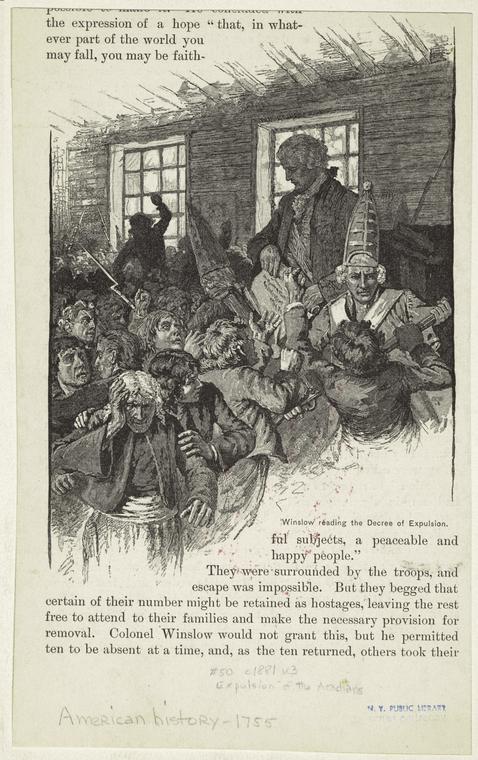

The Acadian Grand-Pré men and boys up to ten years old were summoned to St-Charles-des-Mines, by Lt.-Col. John Winslow of the English Army. Once the men and boys were in the church, it was locked from the outside with the English Army surrounding it. Winslow’s orders were read which included “That your Lands and Tennements, Cattle of all Kinds and Live Stock of all Sortes are Forfitted to the Crown with all other your Effects Saving your money and Household Goods and you your Selves to be removed from this his Province.”[1]“The Great Diaspora of 1755,” Acadian & French Canadian Ancestral Home (http://www.acadian-home.org/deportation.html : viewed 26 June 2022). They were also told that they were the “King’s Prisoners.” These orders were in English and had to be interpreted as the Acadians spoke French and few spoke English. One English soldier recorded the reaction of the Acadians when they heard the orders “Seing themselves so Decoyed the shame and confusion of face together with Anger so altered their countenense that it cant be expressd.”[2]Krista Armstrong, “Forgotten diary sheds new light on Acadian deportation of 1755,” Toronto Star, Krista Armstrong, 26 November … Continue reading

There were five Pierre LeBlancs imprisoned in St-Charles-des-Mines the day the Acadians were told they were to leave.[3]Lucie LeBlanc Consentino, Deportees of Grand-Pre 1755, http://www.acadian-home.org/deport-list.html, viewed 9 Jan 2020. The men were held in the churches across Nova Scotia while waiting for the ships to arrive. Was Anna one of the many women outside the church crying and distraught upon hearing the news? Who else from Anna’s family was locked in the church that day? A brother? Her father? Uncles and grandfather? Anna, like many of the women, probably anxiously took care of the animals and farm while the men were locked in the churches. Most likely, they were scared and worried what the English soldiers would do to them or their husbands, fathers, and sons.

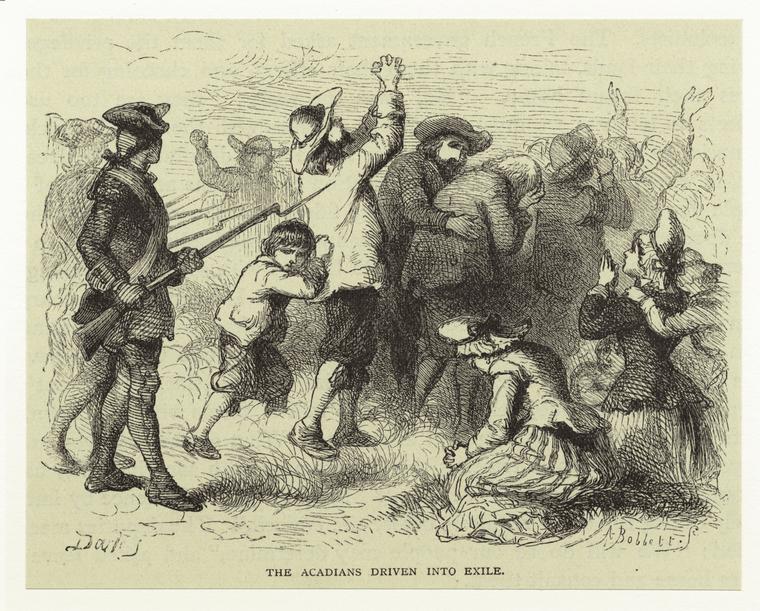

The men held in Grand-Pré were separated into five groups and imprisoned on ships. While walking to their prison, the men were praying. Anna was probably one of the women following the men and praying on her knees for their release.

When it was time for the women and children to board the ships that would take the Acadians away from their beloved L’Acadie, they had to walk about a mile and a half to the deportation site on the Gaspereau River. Children were being carried and the elderly were transported in carts. Did she and Pierre watch the British burn the homes and buildings in Grand-Pré as their ship departed? Anna must have carried that day with her for the rest of her life.

At this time, Anna Landry’s parents are unknown. So many church records were lost or destroyed. She was born between 1731 and 1737.[4]Anne Landry (abt. 1735 – 1808), Wikitree.com (https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Landry-3450#_note-2 : viewed 18 June 2022). She and Pierre probably married between 1751 and 1755 and may have had several young children before the deportation who did not survive for long.

Since Anna’s family was departed to Oxford, Maryland, the assumption is that they had lived in Pisiquid (now Windsor, Nova Scotia) as most of the Acadians who were sent from Grand-Pré on 27 Oct 1755 bound for Annapolis, Maryland were from that area.[5]Paul Delaney, “The Chronology of the Deportations and Migrations of the Acadians 1755-1816,” Acadian & French Canadian Ancestral Home … Continue reading After sailing for six weeks on the sloop Ranger with 263 Acadians (eighty-three more than should have been on the sloop), they arrived in Oxford 8 Dec 1755.[6]“Acadians in Oxford,” Acadians in Were Here (https://acadianswerehere.org/acadians-in-oxford.html : viewed 14 June 2022. Because there were so many more people on the sloop, most belongings could not be brought with them. Prior to boarding the Ranger, they waited several days as there was no room on the sloops Three Friends and Dolphin.

Instructions to the captains of the ships that took the Acadians from Nova Scotia to the American colonies included provisions of “one pound flour and a half pound of bread per day for each person, and a pound of beef per week to each.”[7]Basil Sollers, “Te Acadians (French Neturals) Transported to Maryland, Maryland Historical Magazine, Vol. III, No. 1, March, 1908, p. 9 … Continue reading Sources seem in conflict, but after a fierce storm the Ranger and accompanying ships were found in Boston 5 November 1755 taking shelter. “…those on the Ranger are ‘sickly & their water very bad.’”[8]Basil Sollers, “Te Acadians (French Neturals) Transported to Maryland, Maryland Historical Magazine, Vol. III, No. 1, March, 1908, p. 9 … Continue reading How did Anna and Pierre manage on the ship? Were they huddled in the hold next to family and friends, or were they separated from each other? Did they have young children who did not survive the journey?

The people of Maryland were surprised when three ships jammed with hungry and sick Acadians arrived in Annapolis, Maryland, with no warning. Governor Lawrence had not communicated to the colonies that Acadians would be arriving, so Maryland was not expecting to house and feed so many people. Over 900 Acadians had arrived in three ships. The Protestant community was very much against the Roman Catholics whom they called “Papists.” Additionally, the people of Maryland greatly feared the Acadians since the newspapers in Maryland and Pennsylvania described them as “…secret Enemies, and have encouraged our Savages to cut our throats.”[9]Halifax, August 9, Pennsylvania Gazette (published as The Pennsylvania Gazette), 4 September 1755, … Continue reading The Acadians were lumped into the same lot as the French Army who was fighting with the Mi’kmaq (the first people of Nova Scotia) against the British even though the Acadians declared themselves “French Neutrals” holding no ill feelings toward either side.

The Ranger, now with 208 Acadians on board, was sent to Oxford, Maryland, on the Choptank River, and placed under the supervision of Henry Callister.[10]“The Ships of the Acadian Expulsion,” https://www.acadian.org/history/ships-acadian-expulsion/, viewed 30 Dec 2019. The other ships were sent to Port Tobacco and other areas of Maryland. Soon after their arrival, there were outbreaks of pneumonia and smallpox. Though there were many Catholic families in Maryland, the government did not allow them to house the Acadians. With no land, resources or connections, the refugees from Acadia had no option but to fend for themselves and accept the little charity the government arranged. About 300 of the Acadians who arrived in Maryland did not survive. Acadians in Maryland were restricted from traveling more than ten miles from where they were housed, and local governments could “bind out” their children to local farmers.

How did Anna and Pierre escape from the ravages of pneumonia and smallpox? Was their daughter, Rose born in Pisiquid or Maryland? How was it that Anna, Pierre and Rose survived? Had Pierre been able to find work on a nearby tobacco farm? Or did they have to live in squalor like so many of the Acadians in Maryland did? Was Anna reduced to begging door to door to gain food, clothing, and shelter for her family?

The 7 July 1763 census of Acadians in Oxford, Maryland includes at least four LeBlanc families, twenty Landry families and a sprinkling of Babin families; families that were probably related and would interact together in Louisiana.[11]A digital image of “Recensement des habitants Neutres de Laccadie detanus a Oxford, En Maryland,” taken from Public Archives of Canada; M.G. 5, A-1, Vol. 450, … Continue reading Anna’s family included her husband Pierre, Simon, Rose, and Ludivine. Were Simon and Ludivine their children who were born in Maryland or were they orphans or extended family members? The census record only identifies the spouse and does not record ages. Simon and Ludivine may not have survived the following years since they are not mentioned as living with Anna and Pierre again.[12]Simon LeBlanc and Ludivine LeBlanc are not recorded in future census records nor were they included in Pierre LeBlanc’s succession record, Eileen Larré Behrman, Ascension Parish, … Continue reading

With the end of the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years War) in 1763, the Acadians could relocate, but could not afford the expense. They desperately wanted to return to Nova Scotia but were not allowed. Somehow the Acadians received communication from the Broussards, (who were possibly former neighbors or relatives and who had managed to resettle in Louisiana) suggesting other Acadians follow. The Acadians in Maryland and Pennsylvania wanted to go to Louisiana but did not have the money for passage. Maryland officials eventually provided funding to charter ships so that they could be rid of the Acadians.

Up to this point, Anna’s life has been rather tragic since the deportation but immigrating to Louisiana changes her life for the better. The next posting will describe Anna’s life in Louisiana.

Visit The Friends of Grand-Pré's website https://amis--de--grand--pre-ca.translate.goog/index.htm?_x_tr_sch=http&_x_tr_sl=fr&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=op,sc. This organization maintains the old Sainte-Famille Cemetery (1698-1755) in Falmouth (Pisiquid). Visit https://amis--de--grand--pre-ca.translate.goog/stefamille/buyabrick.htm?_x_tr_sl=fr&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=op,sc&_x_tr_sch=http to purchase a brick to help maintain the cemetery.

References

| ↑1 | “The Great Diaspora of 1755,” Acadian & French Canadian Ancestral Home (http://www.acadian-home.org/deportation.html : viewed 26 June 2022). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Krista Armstrong, “Forgotten diary sheds new light on Acadian deportation of 1755,” Toronto Star, Krista Armstrong, 26 November 2009 (https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2009/11/26/forgotten_diary_sheds_new_light_on_acadian_deportation_of_1755.html : viewed 26 June 2022). |

| ↑3 | Lucie LeBlanc Consentino, Deportees of Grand-Pre 1755, http://www.acadian-home.org/deport-list.html, viewed 9 Jan 2020. |

| ↑4 | Anne Landry (abt. 1735 – 1808), Wikitree.com (https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Landry-3450#_note-2 : viewed 18 June 2022). |

| ↑5 | Paul Delaney, “The Chronology of the Deportations and Migrations of the Acadians 1755-1816,” Acadian & French Canadian Ancestral Home (file:///Users/sinditerrien/Documents/Acadian%20Research%20and%20Sources/Acadia/Chronology%20of%20the%20Deportations%20&%20Migrations%20of%20the%20Acadians%201755-1816%20by%20Paul%20Delaney.webarchive : viewed 18 June 2022). |

| ↑6 | “Acadians in Oxford,” Acadians in Were Here (https://acadianswerehere.org/acadians-in-oxford.html : viewed 14 June 2022. |

| ↑7 | Basil Sollers, “Te Acadians (French Neturals) Transported to Maryland, Maryland Historical Magazine, Vol. III, No. 1, March, 1908, p. 9 (https://books.google.com/books?id=ZiUXAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=maryland+acadians&source=bl&ots=nIPkwHo88i&sig=-2_fLRCNFcPW1QxNJM1ccdthLiA&hl=en&ei=2N_TScTvNZbFtge7xeC9DA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=25#v=onepage&q=maryland%20acadians&f=false viewed 31 Dec 2019). |

| ↑8 | Basil Sollers, “Te Acadians (French Neturals) Transported to Maryland, Maryland Historical Magazine, Vol. III, No. 1, March, 1908, p. 9 (https://books.google.com/books?id=ZiUXAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=maryland+acadians&source=bl&ots=nIPkwHo88i&sig=-2_fLRCNFcPW1QxNJM1ccdthLiA&hl=en&ei=2N_TScTvNZbFtge7xeC9DA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=25#v=onepage&q=maryland%20acadians&f=false viewed 31 Dec 2019). |

| ↑9 | Halifax, August 9, Pennsylvania Gazette (published as The Pennsylvania Gazette), 4 September 1755, (https://infoweb-newsbank-com.nehgs.idm.oclc.org/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&t=pubname%3A10D34C656629FD30%21Pennsylvania%2BGazette&sort=YMD_date%3AA&fld-base-0=alltext&val-base-0=%22neutral%20french%22&val-database-0=&fld-database-0=database&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=1750%20-%201756&docref=image%2Fv2%3A10D34C656629FD30%40EANX-10D80D223AAED3C0%402362307-10D80D2276219310%401&origin=image%2Fv2%3A10D34C656629FD30%40EANX-10D80D223AAED3C0%402362307-10D80D2276219310%401-10D80D231FB62230%40Halifax%252C%2BAugust%2B9 : viewed 22 June 2022) database America’s Historical Newspapers, page 2, column 2. |

| ↑10 | “The Ships of the Acadian Expulsion,” https://www.acadian.org/history/ships-acadian-expulsion/, viewed 30 Dec 2019. |

| ↑11 | A digital image of “Recensement des habitants Neutres de Laccadie detanus a Oxford, En Maryland,” taken from Public Archives of Canada; M.G. 5, A-1, Vol. 450, Folio 445, p. 212 can be viewed at AcadiansWereHere.org (https://acadianswerehere.org/acadians-in-oxford.html : viewed 5 Jun 2022). |

| ↑12 | Simon LeBlanc and Ludivine LeBlanc are not recorded in future census records nor were they included in Pierre LeBlanc’s succession record, Eileen Larré Behrman, Ascension Parish, Louisiana Civil Records 1770-1804 (Conroe, Texas, 1986), p 451-458. |