My Fifth Great-Grandmother

(About 1749 to about 1812)

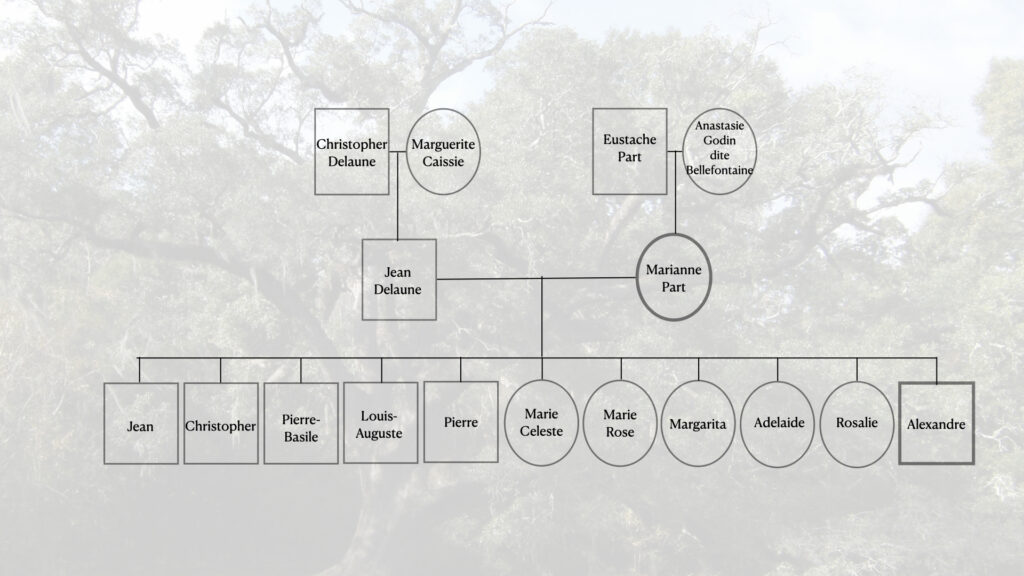

Daughter of Eustache Part and Anastasie Godin dite Bellefontaine

Husband Jean Delaune

Mother of Jean (abt. 1774), Christopher (abt. 1776), Pierre-Basile (abt. 1779), Louis-Auguste (1782), Pierre (abt. 1784), Marie Celeste (abt. 1785), Marie Rose (abt. 1787), Margarita (abt. 1787), Adelaide (abt. 1790), Rosalia (1791), and Alexandre (abt. 1797)

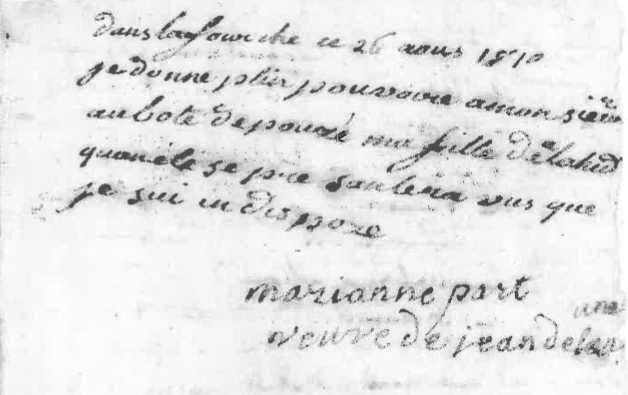

One of my very favorite ancestors, Marianne Part (Pare), my fifth great-grandmother, was an Acadian woman who learned to read and write during a time of great upheaval for Acadians. She signed her name several times between 1773 and 1812 on official documents. Though her name can be spelled many ways, she signed her name as Marianne Part. How did she learn to sign her name? Who taught her? When did she learn? These are questions to consider.

The British and French were in constant conflict over the land the Acadians settled in North America. During an attack by the British when she was a little girl, she was running for her life with her father and grandmother as her own mother was being killed and notably scalped by enemy soldiers. Sometime after, she accompanied her father and grandparents as prisoners to Halifax, Nova Scotia, before being deported to Cherbourg, France. While in France, she married and sadly buried her first four children. Then she and her husband and two children sailed to Louisiana in 1785 where she spent the rest of her life.

There is so much to Marianne’s story, that it should be told over the course of several weeks. I hope you will be as intrigued with her as I am as her life and times are revealed.

The Early Years – A Young Acadian

Marianne Part was born in Acadia between 1749 and 1751 to Eustache Part and Anastasie Godin dite Bellefontaine.[1]Sacramental registers from Point Sainte-Anne are lost. Her marriage record identifies her parents. Archives départementales – Maison de l’histoire de la Manche; Microfimage de … Continue reading She was probably named after her maternal grandmother, Marie-Anne Bergeron. They lived in Point Sainte-Anne which is now Fredricton, New Brunswick.

Because Marianne’s grandfather, Joseph Godin dit Bellefontaine, owned quite a bit of the land in Point Sainte-Anne and was considered a leader in the community, her early childhood was probably very pleasant. She had several brothers and sisters.

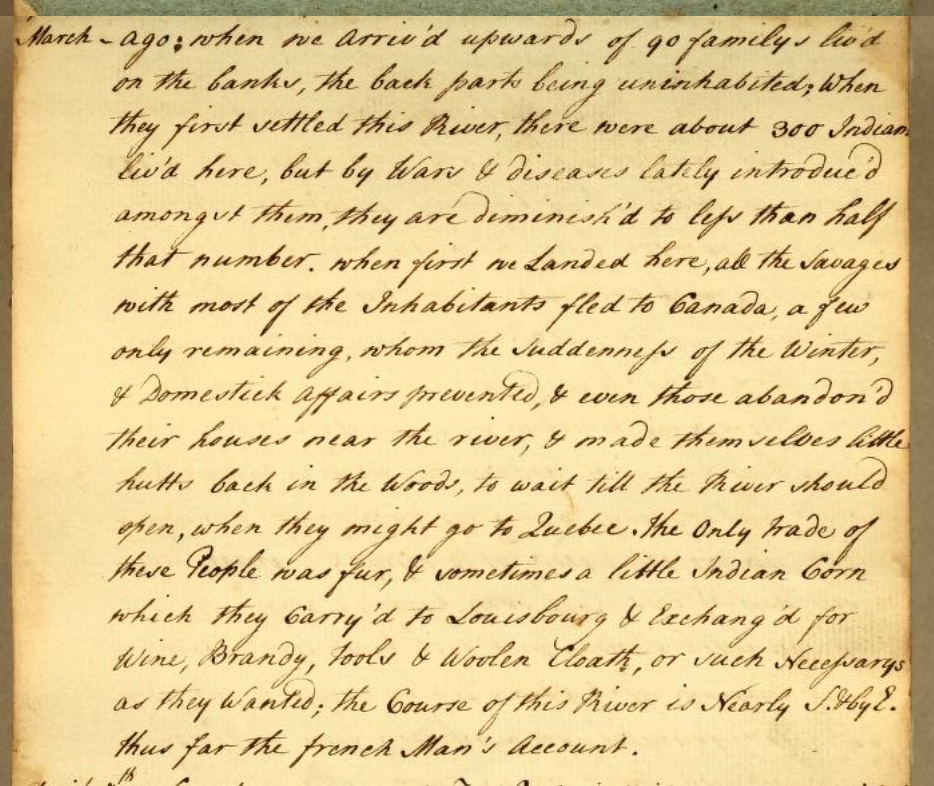

Point Sainte-Anne had been a village of about ninety Acadian families on the St. John River, but with the British encroaching on the area and having built Fort Fredricton nearby, many of the Acadian families had fled north. For unknown reasons, Marianne’s maternal grandparents, her uncle and his family, and her father’s family stayed at Point Sainte-Anne over the winter of 1759. A group of New England Rangers led by Captain Moses Hazen who were working with the British to remove Acadians came upon Marianne’s family while scouting the area.

Marianne’s grandfather, Joseph Godin dit Bellefontaine was a major in the French militia.[2]Joseph Bellefontaine is described as a major in the militia on the Isle of St. Jean. Cherbourg parish records, Registres paroissiaux et d’état civil de la Manche; Archives … Continue reading The men under Captain Hazen became violent when her grandfather and uncle would not take an oath of allegiance to the English. They killed Marianne’s mother, her aunt, and at least two children who were her siblings and cousins. Marianne’s grandfather and uncle witnessed the vicious killing and scalping of their loved ones. Marianne and her brother, Laurent, escaped into the woods with her father and grandmother. This entire violent episode was recorded at least three times. On 5 April 1759, The Pennsylvania Gazette published an extract of a letter from Fort Fredricton date 3 March 1759 which said that six prisoners and six scalps were taken.[3]”Extract of a Letter from Fort Frederick, St. John’s River, March 10, 1759,” The Pennsylvania Gazette, 5 April 1759, page 2, col. 3 and page 3 col. 1; Newspaper.com … Continue reading It does not mention that the scalps were those of six women and children. An unknown soldier of the Seven Years War wrote the following in his journal:

March 6th (1759) “Lt. Hazzen return’d having been up as far as St. Ann’s, a very pretty French settlement of about 140 houses, he did not find any inhabitants, the houses he burned; on his return through he woods, he chance’d to fall in with one poor family, 6 he made prisoners & after the rude custom of the savages, whom the Americans copy, scalped 2 women & 2 children. The oldest prisoner was a man of some Consequence & had a commission as Major of Militia, he gave us the following account of the River St. John…[4]Seven Years’ War journal of the proceedings of the 35th Regiment of Foot; 6 March entry; Archive.org, digital images 53-54 (https://archive.org/details/sevenyearswarjou00flet/page/n1/mode/2up : … Continue reading

The third accounting of this tragic event was from Joseph Godin dit Bellefontaine twenty some odd years later in an interview he gave in Cherbourg. All accounts are essentially the same though Joseph’s account is more graphic, as it should be.[5]A transcript written in French of Joseph Bellefontaine’s petition for a pension documents the killing of his daughter and can be viewed at Septentrion.qc.ca, … Continue reading

Family members with Marianne’s grandfather and uncle were taken as prisoners to Fort Royal. Marianne and those that escaped made their way to Fort Royal and joined the others as prisoners. While the British decided what to do with them, they were sent to Boston, Massachusetts, before being taken to Halifax in Nova Scotia.

While they were imprisoned, they were treated very harshly. Marianne and her family were finally sent to Cherbourg, France, after a brief stay at Georges Island in the harbor near Halifax.

How does a child of eight or nine years of age overcome the violent death of her mother, aunt, siblings and cousins? Marianne was placed on board a ship with her grandparents, father and brother to cross the Atlantic Ocean where she started a life in a place very foreign to her.

The Bellefontaines were considered an elite Acadian family because of Joseph’s connections as well as his father and grandfather’s connections to the French military and leading positions in Acadia. In Cherbourg, they were probably housed near the Acadian d’Etremont family who were of nobility. If that was so, it is possible that Marianne, a young girl in need of some occupation in Cherbourg, was friendly with the d’Etremonts and learned to read and write from them.

When she was about twenty-three years old, Marianne married Acadian Jean Delaune at Sainte Trinite in Cherbourg on 18 February 1773. The church sacramental register contains the marriage record with her signature. Her brother, Laurent, attended the wedding and signed his name but there is no signature or marque for her father or Jean Delaune. Interestingly, Jean’s brother, Christopher, also signed the register. Sainte Trinite, although it was ransacked during the French Revolution, remains to this day in Cherbourg.[6]Microfimage de L’Etat Civil de la Manche (France) Cherbourg, Collection 5 Mi 1453-1554, Cherbourg, Baptêmes, Mariages, 1771-1775, images 148 and 149 of 366, Maison de l’histoire de la … Continue reading

With Marianne’s marriage, her childhood formally ends. The next post will be about her life in France with her husband Jean Delaune.

References

| ↑1 | Sacramental registers from Point Sainte-Anne are lost. Her marriage record identifies her parents. Archives départementales – Maison de l’histoire de la Manche; Microfimage de L’Etat Civil de la Manche (France) Cherbourg, digital images 148 and 149 of 366 (http://www.archives-manche.fr/ark:/57115/a011288085768pCJpVF/d5bb518951, viewed 3 August 2022). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Joseph Bellefontaine is described as a major in the militia on the Isle of St. Jean. Cherbourg parish records, Registres paroissiaux et d’état civil de la Manche; Archives départmentales-Maison de l’histoire de la Manche, image 35 of 262,. (http://www.archives-manche.fr/ark:/57115/a011288085768oM9wq4/69f80ce525 : viewed 4 August 2022). |

| ↑3 | ”Extract of a Letter from Fort Frederick, St. John’s River, March 10, 1759,” The Pennsylvania Gazette, 5 April 1759, page 2, col. 3 and page 3 col. 1; Newspaper.com (https://www.newspapers.com/image/39396445?_gl=1jsecs9_up*MQ..&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI-oTn2sG3-QIVUsqzCh0QigEJEAMYASAAEgKYjfD_BwE : viewed 8 August 2022). |

| ↑4 | Seven Years’ War journal of the proceedings of the 35th Regiment of Foot; 6 March entry; Archive.org, digital images 53-54 (https://archive.org/details/sevenyearswarjou00flet/page/n1/mode/2up : viewed 8 August 2022). |

| ↑5 | A transcript written in French of Joseph Bellefontaine’s petition for a pension documents the killing of his daughter and can be viewed at Septentrion.qc.ca, (https://www.septentrion.qc.ca/acadiens/documents/819), Document 1774-01-15a. This transcript was taken from Archives Nationales du Canada, MG6 A15, series C [microfilm F 849] // AD Calvados [Caen], C 1020. Bellefontaine dit Beauséjour, Acadian, major of the Saint-Jean River militias // De la Rue de Francy, commissioner of classes in Cherbourg. |

| ↑6 | Microfimage de L’Etat Civil de la Manche (France) Cherbourg, Collection 5 Mi 1453-1554, Cherbourg, Baptêmes, Mariages, 1771-1775, images 148 and 149 of 366, Maison de l’histoire de la Manche; Register de Baptêmes et Mariages l’Elise de Cherbourg, 1773, Jean Delaune & Marie Part, p. 171-172 (http://www.archives-manche.fr/ark:/57115/a011288085768pCJpVF/d5bb518951 : viewed 17 March 2023). |