My Seventh Great-Grandmother

(1706 to 1779)

Daughter of Barthelemy Bergeron dit d’Amboise and Genevieve Serrault

Husband Joseph Godin dit Bellefontaine

Mother of Anastasia and Michel and probably other children.

Note: There are four women in this article with the name Marie-Anne: Marie-Anne Bergeron d’Amboise who married Joseph Godin dit Bellefontaine and her younger sister Marie-Anne Bergeron who married Jacques Godin (Joseph’s brother); Marianne Part, the elder Marie-Anne's granddaughter; and Marie Anne Gautier, godmother to the younger Marie-Anne Bergeron. This article focuses on the elder Marie-Anne Bergeron d’Amboise who married Joseph Godin dit Bellefontaine.

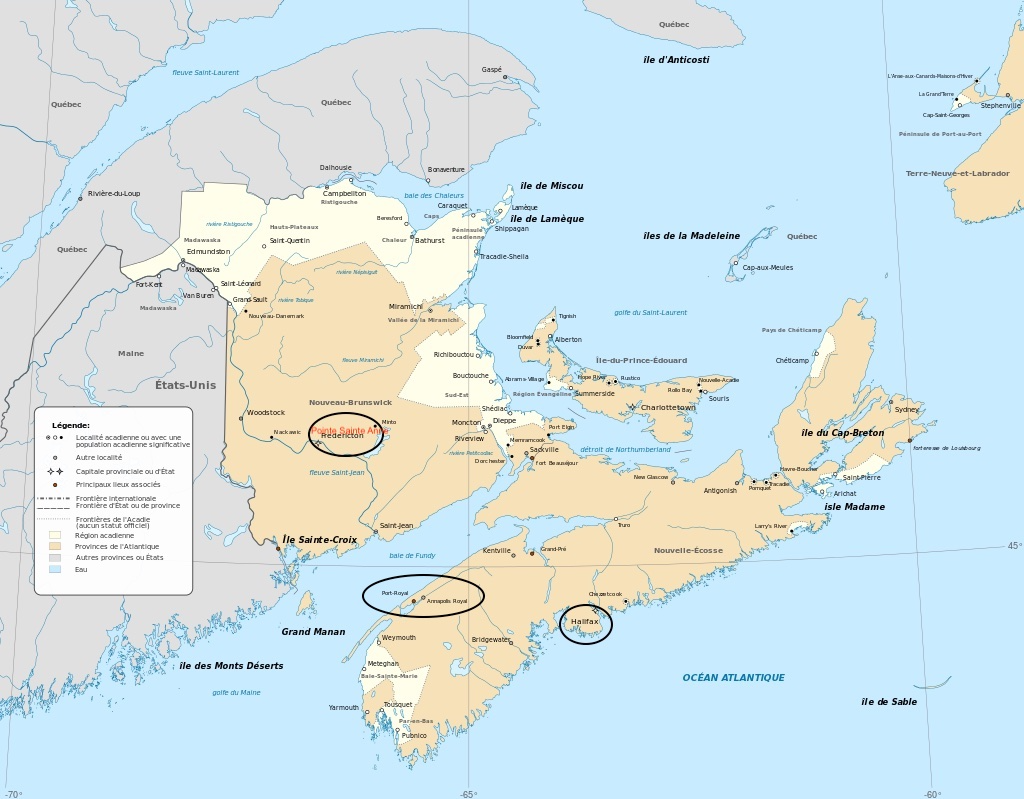

While held hostage in Boston, Acadians Barthelemy Bergeron dit d’Amboise and Genevieve Serrault’s daughter, Marie-Anne Bergeron d’Amboise, was born. Through a prisoner exchange, the Bergeron family returned to Port Royal in Nova Scotia.[1]Stephen A. White, English Supplement to the Dictionnaire Généalogique Des Familles Acadiennes, (Moncton, New Brunswick: Université de Moncton, 2000), p. 27, (Moncton, New Brunswick: … Continue reading Though she was born in Boston 24 June 1706, she was baptized at St. Jean-Baptiste in Port Royal a few months later. Her godparents were Pierre Pellerin and Françoise Moyse.[2]Nova Scotia Archives, An Acadian Parish Remembered, The Registers of St. Jean-Baptiste, Annapolis Royal, 1702-1755, digital image, https://novascotia.ca/archives/acadian/archives.asp?ID=159, viewed … Continue reading

Marie-Anne’s father was a French soldier, possibly a petit noble, and merchant, trading with New Englanders. Marie-Anne’s parents were among the very first settlers of Nouvelle-France and Acadia (what is now Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia).[3]Richard J. Bergeron, “Three Acadian Generations The First Bergeron d’Amboises in the Americas” acadian.org (https://www.acadian.org/genealogy/families/first-bergeron-damboises-americas/ : … Continue reading Throughout Marie-Anne’s life, Acadia was fought over by the English and French and changed hands many times.

A few years after Marie-Anne’s birth, Barthelemy and Genevieve had another daughter whom they named Marie-Anne also. She too was baptized at St. Jean-Baptiste 24 Sep 1709 with godparents of Pierre Gautier and Marie Anne Gautier.[4]Nova Scotia Archives, An Acadian Parish Remembered, The Registers of St. Jean-Baptiste, Annapolis Royal, 1702-1755, https://novascotia.ca/archives/acadian/archives.asp?ID=301, viewed 13 … Continue reading Both daughters were baptized by Justinien Durand. I wonder how family distinguished each daughter. Was one Marie and the other Anne? Did one go by Marie-Anne while the other was given a pet name such as Annette?

Living in Port Royal in Nova Scotia in 1714, Marie-Anne had two sisters and three brothers.[5]The original census can be found at Acadian Census microfilm C-2572 of the National Archives of Canada “Acadie Recensements 1671 – 1752”, beginning at Image 239, DAMBOUC (sic) and wife, 3 … Continue reading The Bergeron family left Port Royal and probably crossed the Bay of Fundy to settle in Pointe Sainte Anne on the St. Jean River. The elder Marie-Anne married Joseph Godin dit Bellefontaine around 1726.[6]Richard J. Bergeron, “Three Acadian Generations The First Bergeron d’Amboises in the Americas” acadian.org … Continue reading The younger Marie-Anne married Jacques-Philippe Godin dit Bellefeuille, Joseph’s brother. Barthelemy Bergeron d’Amboise and Gabriel Godin, father of Joseph and Jacques-Philippe, were friends, so it would not be at all surprising for their children to marry. Marie-Anne had at least two children, Anastasia born around 1730, and Michel born around 1733.[7]In 1767, Michel was noted to be thirty-four years old, making his year of birth around 1733. “Lettre de M. Mistral au Due de Praslin, 1906,” in Gaudet, … Continue reading It is possible that she had other children.

In 1749, Charles Deschamps de Boishébert, officer of the French colonial troops, commissioned Marie-Anne’s husband, Joseph, as major of militia along the St. Jean River.[8]George MacBeath, “Godin, Bellefontaine, Beauséjour, Joseph,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003 … Continue reading Marie-Anne’s son, Michel, was also placed in command. Joseph had a large tract of land at Pointe Sainte-Anne and the family most likely lived a comfortable life for a while. Given her husband’s position, it is likely that Marie-Anne had nicer clothes and a nicer home than the other women of Pointe Sainte-Anne. It is also likely, as was common among the financially well off during that time, that Marie-Anne had servants to assist with her household and everyday chores.

Between 1755 and 1760, many Acadians were trying to escape the deportation by the British. Some were captured and were sent to different places in the American colonies; others were sent to England and finally, many were sent to France. There were also groups of Acadians who escaped to Quebec and the woods in New Brunswick. Whenever she could, Marie-Anne, as wife of an influential man and commander of the militia, most likely would have given food and clothing to Acadians who passed through Pointe Sainte Anne, that is, until it was her family’s turn to be captured and deported.

Marie-Anne had the unthinkable experience of witnessing her daughter’s death and scalping in February 1759. Whether or not she saw everything that went on with the gruesome murder by British soldiers that day at Pointe Sainte Anne, Marie-Anne and her son-in-law, Eustache Part, were able to keep two of her grandchildren safe. Marianne Part and Laurent Part were the children of Anastasia Godin dit Bellefontaine, who was killed by soldiers looking to rid the area of Acadians. Also killed that day were her son’s wife and their son.[9]“Lettre de M. Mistral au Due de Praslin, 1906,” in Gaudet, Placide, Généalogie des famillies acadiennes: avec documents: rapport concernant les … Continue reading Marie-Anne’s husband and son, Michel, were taken as prisoners. Having no food or clothing, Marie-Anne, along with Eustache Part and the surviving children, Marianne and Laurent, surrendered to the British and joined her husband in prison. They were sent to George’s Island in the Halifax harbor, which was known for the harsh treatment of prisoners.

Several months later, Marie-Anne and her family were sent to England but did not disembark. They were sent next to Cherbourg, France.[10]Réfugiés, Contient la liste des habitants de l’Ile Royale, de l’Ile Saint-Jean et de l’Acadie réfugiés à Cherbourg. … Continue reading Their living conditions in Cherbourg were not much better than they had been when they were imprisoned in Halifax. Other Acadians who were deported were also in Cherbourg. Marie-Anne probably helped Eustache bring up his children since their mother was dead. She probably made sure they were fed and clothed, said their prayers, and likely taught them Acadian customs and traditions.

In March of 1767, Monsieur Mistral, commissioner of the Navy at LeHavre, visited Marie-Anne and her husband and wrote a letter to the Duke of Praslin of his findings. He reported that both were bed-ridden. Each were receiving a pension of about 300 livres from the French government. Joseph told Mistral that he was the son of Gabriel Bellefontaine, officer on the ships of the King in Canada and his mother was Angelique Roberte Jeanne. Joseph reported that Marie-Anne was the daughter of Barthelemy Bergeron who was from Amboise in France and her mother was Delle Cerau (Genevieve Serrault) of St. Aubin. Joseph said that he was a major of all militias of the River St. Jean since 1749 and that he had possessed several leagues of land. He also said that he witnessed the massacre of his daughter and her three children by the English when they tried to make him change allegiance.[11]“Lettre de M. Mistral au Due de Praslin, 1906,” in Gaudet, Placide, Généalogie des famillies acadiennes: avec documents: rapport concernant les … Continue reading

Marie-Anne’s son, Michel, was also interviewed by Mistral. He stated that his wife and son had been massacred by the British when his sister and her children had been killed.[12]“Lettre de M. Mistral au Due de Praslin, 1906,” in Gaudet, Placide, Généalogie des famillies acadiennes: avec documents: rapport concernant les … Continue reading At the end of the month, Michel died and was buried in Cherbourg.[13]Cherbourg Registres paroissiaux et d’état civil, 1763-1767, E39, Archives départementales de la Manche; digital image 134 of 152 … Continue reading Marie-Anne must have been so sad to have lost her son. Thankfully, Eustache Part, Marie-Anne’s widowed son-in-law, also lived in Cherbourg with his daughter Marianne and son Laurent.[14]“Lettre de M. Mistral au Due de Praslin, 1906,” in Gaudet, Placide, Généalogie des famillies acadiennes: avec documents: rapport concernant les … Continue reading

In September 1772, when the French government surveyed the Acadians in France, Joseph, seventy-seven and Marie-Anne, sixty-seven were very ill and still in Cherbourg.[15]Milton P. Rieder, The Acadians in France, 1762-1776; Rolls of the Acadians living in France distributed by towns for the years 1762 to 1776 (Metaire, Louisiana, 1967), p. 37; digital … Continue reading Marie-Anne’s granddaughter, Marianne Part, married Jean Delaune in 1773 at Ste. Trinite in Cherbourg.[16]Sacramental registers from Point Sainte-Anne are lost. Archives départementales – Maison de l’histoire de la Manche; Microfimage de L’Etat Civil de la Manche … Continue reading Hopefully, Marie-Anne was healthy enough to attend the wedding. In 1775, Marie-Anne and Joseph would be alone in Cherbourg as family members departed with other Acadians to participate in the farming project the Marquis Perusse des Car proposed for the Acadians in Poitou, France.[17]Milton P. Rieder, The Acadians in France, 1762-1776 (Metaire, Louisiana, 1967) p. 57; digital … Continue reading It must have been a sad day when the family said what was probably their final goodbyes.

Joseph died in 1776 leaving Marie-Anne to survive three more years without family. She died in Cherbourg 6 September 1779. More than twenty years passed from the time Marie-Anne had left L’Acadie and saved her two grandchildren. Marie-Anne may have experienced a somewhat privileged childhood because of her father’s position and rank in Nouvelle-France. The first thirty years of her married life were probably also somewhat fortunate. But she suffered greatly from the death of her daughter in 1759 until she died. Hopefully, she found some peace through her Catholic faith. Whether or not she knew it, she was blessed with many great-grandchildren and descendants through Anastasia’s daughter Marianne Part.

References

| ↑1 | Stephen A. White, English Supplement to the Dictionnaire Généalogique Des Familles Acadiennes, (Moncton, New Brunswick: Université de Moncton, 2000), p. 27, (Moncton, New Brunswick: Université de Moncton, 2000), p. 27. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Nova Scotia Archives, An Acadian Parish Remembered, The Registers of St. Jean-Baptiste, Annapolis Royal, 1702-1755, digital image, https://novascotia.ca/archives/acadian/archives.asp?ID=159, viewed 13 September 2022. |

| ↑3 | Richard J. Bergeron, “Three Acadian Generations The First Bergeron d’Amboises in the Americas” acadian.org (https://www.acadian.org/genealogy/families/first-bergeron-damboises-americas/ : viewed 18 September 2022). |

| ↑4 | Nova Scotia Archives, An Acadian Parish Remembered, The Registers of St. Jean-Baptiste, Annapolis Royal, 1702-1755, https://novascotia.ca/archives/acadian/archives.asp?ID=301, viewed 13 September 2022. |

| ↑5 | The original census can be found at Acadian Census microfilm C-2572 of the National Archives of Canada “Acadie Recensements 1671 – 1752”, beginning at Image 239, DAMBOUC (sic) and wife, 3 sons, 3 daughters, image 243 (https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c2572/243 : viewed 16 September 2022). |

| ↑6 | Richard J. Bergeron, “Three Acadian Generations The First Bergeron d’Amboises in the Americas” acadian.org (https://www.acadian.org/genealogy/families/first-bergeron-damboises-americas/ : viewed 18 September 2022). |

| ↑7 | In 1767, Michel was noted to be thirty-four years old, making his year of birth around 1733. “Lettre de M. Mistral au Due de Praslin, 1906,” in Gaudet, Placide, Généalogie des famillies acadiennes: avec documents: rapport concernant les archives canadiennes pour l’année 1905, (Ottawa: Archives canadiennes, 1906), p.198-199; digital image, archive.org (https://archive.org/details/gnalogiedesf00gaud/page/198 : viewed 26 September 2022). |

| ↑8 | George MacBeath, “Godin, Bellefontaine, Beauséjour, Joseph,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003 (http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/godin_joseph_4E.html : viewed 22 September 2022). |

| ↑9 | “Lettre de M. Mistral au Due de Praslin, 1906,” in Gaudet, Placide, Généalogie des famillies acadiennes: avec documents: rapport concernant les archives canadiennes pour l’année 1905, (Ottawa: Archives canadiennes, 1906), p.198-199; digital image, archive.org (https://archive.org/details/gnalogiedesf00gaud/page/198 : viewed 26 September 2022). |

| ↑10 | Réfugiés, Contient la liste des habitants de l’Ile Royale, de l’Ile Saint-Jean et de l’Acadie réfugiés à Cherbourg. Centre des archives d’outre-mer (France) vol. 38, Government of Canada, Centre des archives d’outre-mer (France) vol. 38, Mémoire, non signé, intitulé Image 20 of 29. |

| ↑11, ↑12, ↑14 | “Lettre de M. Mistral au Due de Praslin, 1906,” in Gaudet, Placide, Généalogie des famillies acadiennes: avec documents: rapport concernant les archives canadiennes pour l’année 1905, (Ottawa: Archives canadiennes, 1906), p.198-199; digital image, archive.org (https://archive.org/details/gnalogiedesf00gaud/page/198 : viewed 26 September 2022). |

| ↑13 | Cherbourg Registres paroissiaux et d’état civil, 1763-1767, E39, Archives départementales de la Manche; digital image 134 of 152 (https://www.archives-manche.fr/arkotheque/visionneuse/visionneuse.php?arko=YTo1OntzOjEwOiJ0eXBlX2ZvbmRzIjtzOjExOiJmYWNldHRlc19lcyI7czo0OiJyZWYxIjtpOjI7czo0OiJyZWYyIjtzOjY6IjJfNDkwNiI7czo0OiJyZWYzIjtzOjI6IjE0IjtzOjk6InNvcnRBcnJheSI7YTozOntpOjA7czo5OiJDaGVyYm91cmciO2k6MTtzOjQ6IjE3NjMiO2k6MjtzOjIxOiJhZDUwX2V0YXRjaXZpbCMyXzQ5MDYiO319&altoInput=#uielem_move=-1170%2C10&uielem_rotate=F&uielem_islocked=0&uielem_zoom=213 : viewed 28 September 2022). |

| ↑15 | Milton P. Rieder, The Acadians in France, 1762-1776; Rolls of the Acadians living in France distributed by towns for the years 1762 to 1776 (Metaire, Louisiana, 1967), p. 37; digital image archive.org (https://archive.org/details/acadiansinfrance0000ried/page/71 : viewed 25 September 2022). |

| ↑16 | Sacramental registers from Point Sainte-Anne are lost. Archives départementales – Maison de l’histoire de la Manche; Microfimage de L’Etat Civil de la Manche (France) Cherbourg, digital images 148 and 149 of 366 (http://www.archives-manche.fr/ark:/57115/a011288085768pCJpVF/d5bb518951, viewed 3 August 2022). |

| ↑17 | Milton P. Rieder, The Acadians in France, 1762-1776 (Metaire, Louisiana, 1967) p. 57; digital image archive.org (https://archive.org/details/acadiansinfrance0000ried/page/111 : viewed 12 August 2022). |