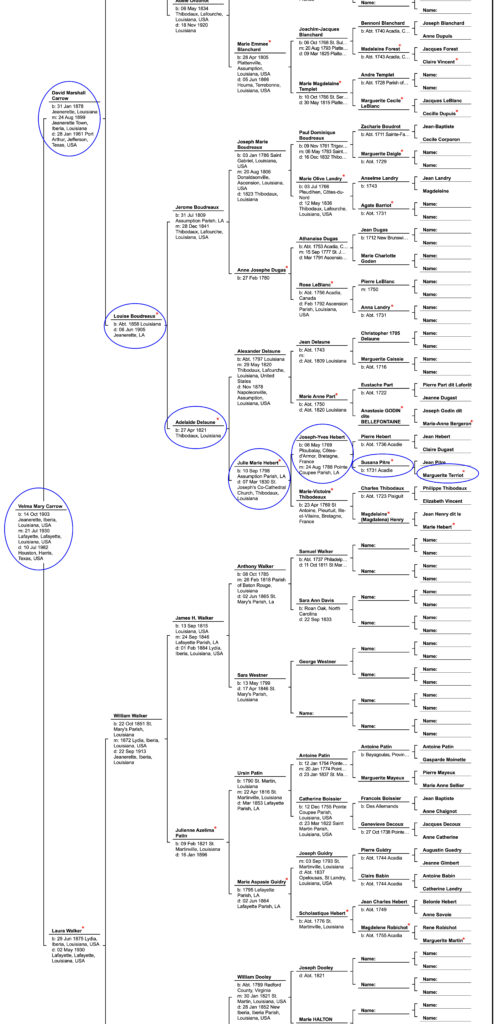

My Seventh Great Grandmother

(about 1701-1758)

Wife of Jean Pitre

Mother of Marie, Elizabeth, Suzanne, Jean, Pierre, Ann, Anselme (there may be other unknown children)

Died at sea along with her husband during the deportation crossing.

The cruelty of Governor Lawrence’s decision to deport Acadians from Nova Scotia in 1755 and the British policy to deport Acadians from Île Saint Jean in 1758 cannot be overstated. So many Acadians died during these deportations either from disease, starvation or drowning—at least two ships sank with approximately 700 Acadians on board.

Fort Louisbourg was on Île Royale, what is now Cape Breton Island. The fort fell to the British in 1758 during the French and Indian War, also known as the Seven Years War.

In 1752, Marguerite Terriot and Jean Pitre lived on Île Saint Jean at Riviere-du-Ouest with six of their children, three sons and three daughters ages 14 to 30 years old.[1] Their daughter Suzanne Pitre, married to Baptists Olivier Henry and their three daughters, lived nearby. The population of Riviere-du-Ouest was mostly Henrys, Pitres and some Terriots. Marguerite and Jean arrived there in 1750 or 1751 because the British had been encroaching on the lands Acadians had developed over the previous seventy-five years or so. Before going to Île Saint Jean, they may have lived near the Minas Basin, Cobequit, Piziquid or Beaubassin as there were Terriots and Pitres there who signed an Oath of Allegiance in 1730.[2]

At least fourteen ships left Île Saint Jean in early November of 1758, some bound for France, others bound for England. The ships were overcrowded as British officials greatly miscalculated the number of Acadians living on the island. Towards the end of November, some of the ships met devastating storms that damaged them. Not all the ships made it to their destinations, in particular the Violet and the Duke William.

It is unknown which ship Marguerite and Jean were on when they were deported from Île Saint Jean. It is known that they did not make it to France or England. They died at sea during the crossing from Île Saint Jean to France either by disease and starvation or drowned in sinking of the Violet or The Duke William. Their names were not on any of the lists taken in Saint-Malo when the Acadians arrived, so they probably were not on one of the five ships that made it to Saint-Malo.[3] Of the 1,000 or so Acadians who were on the five ships that landed in Saint-Malo in January 1759, at least 373 passengers died at sea or soon after arrival.[4] When Suzanne learned of her parents’ death, she must have been devastated. Not only would there be no reunion to celebrate, but there would not even be a grave for Suzanne to visit.

If Marguerite Terriot and Jean Pitre died from disease or starvation during the crossing, then a ceremony on the ship was probably held. Their bodies would have been sewn in a shroud made of sail cloth or something similar. Prayers would have been said over their bodies. Then they would have been weighted down and slid into the sea. Sailors were superstitious of deaths on board a ship. They thought a death on board caused storms. They feared the ship would be haunted, so bodies did not stay on ships for long.

Marguerite and Jean may have been on one of the ships that sank. Four hundred Acadians perished on the Violet and 300 passengers perished on the Duke William when storms took those ships. An extract of a letter written by Captain William Nicholls was published in the Pennsylvania Gazette on 19 April 1759. Nicholls was part owner and captain of Duke William. He also wrote a manuscript of the horrific events that occurred which was published in the Naval Chronicle, Volume 18, in 1807, forty-eight years later. His December 16th letter of 1758 described the events that took place on the Duke William before it sank.[5]

The opening lines of Nicholls’s 1758 letter states that 300 French Neutrals were left aboard the Duke William at 4 o’clock in the afternoon on 13 December and he expected that it would have sunk completely by 8 o’clock. The ship had sprung a leak on 29 November. Passengers were helping to bail water and man the pumps. There was up to five feet of water in the hold. Everything must have been ruined, including food. The Acadians helped to pump and bail water from the ship for days in near-freezing temperatures. For a brief time, they had the water problem under control; but on 11 December, the water burst through again.

In the manuscript published in the Naval Chronicle, Nicholls further described the catastrophe. When it was realized that the ship could not be saved, Father Girard of Point Prim on Ile Saint-Jean, who was on the ship, was notified. The decks were expected to blow. He gave the Acadians absolution. Nicholls said, “I think a more melancholy scene cannot be supposed, than so many people, hearty, strong, and in health, looking at each other with tears in their eyes, bewailing their unhappy condition.” He further described the situation as “…the seeming distraction of the poor unhappy children, clinging to their mothers, and the wives hanging over their husbands, lamenting their miserable fate.”[6]

Though the Acadians had accepted their fate, they were horribly tormented when two ships were seen but did not respond to the distress signals the Duke William had displayed. A third ship sailed nearby a few hours later, but also ignored their cries for help. Because it was war time, the ships may have been overly cautious about assisting a distressed ship.

Nicholls wrote ,

“The French then gave over all hopes, and said, God had forsaken them, and they were resigned to death. As in the terms of the Voyage under our misfortunes, they had behaved with the greatest intrepidity, so in there last moments, they behaved with the greatest Fortitude; for seeing our attempts were frustrated, they came and embraced me, saying, they were truly sensible that I, with all my people, had done all in our power to save the ship, and their lives, but as I could be of no farther service to them, begged I would save my own life and my men.”[7]

Father Girard was transferred to the Richard and Mary with the captain and crew of the ship. Once the captain, crew, and Father Girard were safely on the smaller boats, Nicholls continued, the Acadians “… waving us to be gone, almost broke our hearts.”

There was one miraculous event. Four Acadians had taken a jolly boat from the Duke William and cast it overboard. They survived and arrived in Falmouth. They told Nicholls that “The ship swam till it fell a calm, and as she went down her decks blew up. The noise was like the explosion of a gun, or a loud clap of thunder.”[8]

Acadians on the Violet, experienced a more violent sinking. Their ship had been taking on water for days. In the manuscript published in the Naval Chronicle, Captain Nicholls said that he had communicated with Captain Sugget of the Violet with 500 French on board 10 December. Sugget told Nicholls “…they had a great deal of water in the ship, her pumps were choked, and he was much afraid that she would sink before morning.”[9] The next day, they found “the Violet on her broad-side…the fore yard broke in the slings, the foretopsail set, and her crew endeavoring to free her of the mizen mast…” Then a heavy storm blew in for at least ten minutes. When the storm passed, the Violet was gone.[10] The Acadians on the Duke William were very distressed from seeing the Violet no more, realizing their family, friends and neighbors had vanished so quickly.

If Marguerite was on a ship that sank, how frightening to realize that your death was near and it would be by drowning. Did the Acadians join hands when the ships were going down? Maybe family groups huddled together, kissed each other with love and tenderness and then prayed for God to have mercy on them. The loss incurred by this branch of Pitres was huge. Not only had Jean and Marguerite lost their own lives, but the death toll included at least four of their children, four sons-in-law, and nineteen grandchildren.[11]

Marguerite’s parents cannot be proved at this time. Very few Acadian church records survived the deportation. They were either destroyed, lost during deportation, or went down with the ships that sunk. Without knowing who Marguerite’s parents were, this ends the line of Velma Mary Carrow Provost to Marguerite Terriot Pitre.

[1] Report Concerning Canadian Archives for the Year 1905, Archive.org, p. 82. https://archive.org/details/reportconcerning21publ/page/n193/mode/2up : viewed 30 November 2023.

[2] Placide Gaudet, Acadian Genealogy and Notes, pgs. 77-81; Canadiana, (https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.98644 : viewed 2 December 2023) images 167-171.

[3] Fonds de l’Inscription maritime de Saint-Servan [France] : C-4619;100031; MG6 C2 Library and Archives Canada / Bibliothèque et Archives Canada; https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c4619 images 165-226. Roll of the Habitants of Ile St. Jean – Saint Malo the 23 January 1759 the five boats Anglais le Yarmouth, la Patience, Le Mathias, la Restoration and the John & Samuel.(https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c4619/165 : viewed 27 November 2023)Jean Pitre and Marguerite Terriot did not appear on Rolle general des habitans de l’isle Royale et de l’isle St. Jean pour les 6 derniers mois 1759 distrivue pas paroisses (images 226-265 https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c4619/226 : viewed 27 November 2023).

[4] Rolle general des habitans de l’isle Royale et de l’isle St. Jean pour les 6 derniers mois 1759 distrivue pas paroisses (image 287 https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c4619/287 : viewed 27 November 2023).

[5] ”To the Printers of the Pennsylvania Gazette,” The Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania , Thursday, April 19, 1759, cols.1 & 2; (https://www.newspapers.com/image/39396758/?terms=violet&match=1 : viewed 1 December 2023). The letter was also printed in the London Magazine, December 1758, p. 655, which can be accessed from HathiTrust at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015021267516&seq=719. An account with Newspapers.com may be needed to view the article.

[6] “Narrative of the Voyage and Loss of The Duke William, Transport” The Naval chronicle : containing a general and biographical history of the royal navy of the United kingdom with a variety of original papers on nautical subjects (London: J. Gold, 1807) 18:308-309; (https://archive.org/details/navalchronicleco18londiala : viewed 4 December 2023).

[7] ”To the Printers of the Pennsylvania Gazette,”The Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania , Thursday, April 19, 1759, cols.1 & 2; (https://www.newspapers.com/image/39396758/?terms=violet&match=1 : viewed 1 December 2023). The letter was also printed in the London Magazine, December 1758, p. 655, which can be accessed from HathiTrust at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015021267516&seq=719.

[8] “Narrative of the Voyage and Loss of The Duke William” The Naval Chronicle 18:409 (https://archive.org/details/navalchronicleco18londiala : viewed 4 December 2023).

[9] Ibid., 306.

[10] Ibid., 308.

[11] “Marguerite Theriot (abt. 1701 – 1758) Wikipedia (https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Theriot-3 : viewed 3 December 2023).